History of the Minnesota River

The Minnesota River, formerly named St. Peter’s River, flows more than 300 miles before entering the Lower Minnesota River Watershed District (LMRWD). The river lies in a broad, deep valley that the River Warren carved as it drained the outflow from Lake Agassiz; the River Warren and Lake Agassiz were glacial features that occurred more than 10,000 years ago. According to Featherstonhaugh (1847) the American Indian name of the St. Peter’s River is Minnay Sotor, or “Turbid Water,” because the water looked as if whiteish clay had been dissolved in it. The US Congress voted in 1852 that the official name of the river should be Minnesota (Minnesota Historical Society [MNHS] n.d.).

For centuries, the Dakota American Indian community has maintained strong connections to the Minnesota River and its many tributaries, prospering while coexisting with the natural resource community (Minnesota River Basin Data center [MRBDC] n.d.). Today, the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux community, which includes direct descendants of the Dakota people, is located along the lower end of the Minnesota River near the Twin Cities. The community concentrates on a wide range of services, including those related to protecting and restoring the natural environment back to pre-European American settlement conditions. These efforts include prairie restoration, drinking water protection, and energy production from natural materials (MRBDC n.d.).

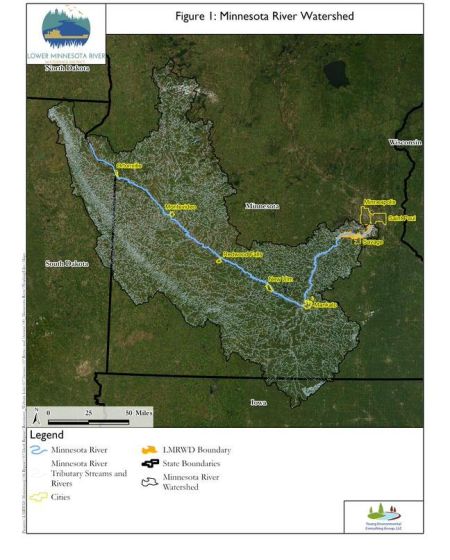

The Minnesota River watershed is nearly 17,000 square miles ([mi2] 44,000 square kilometers [km2]). It drains much of western and southern Minnesota. The main channel of the river starts near northwestern South Dakota; flows southeast toward Mankato, Minnesota; then flows north-northeast to where it meets the Mississippi River in the Twin Cities, Minnesota. The Minnesota River doubles the flow of the Mississippi River where they join (Musser, Kudelka, and Moore 2009). Nearly all the land that was prehistorically prairie, open range, or wooded has been converted to agricultural land uses (Musser, Kudelka, and Moore 2009). The desire to increase tillable acreage resulted in filling or draining many of the wetlands that originally covered the land. Changing the landscape is implicated in changing the flow characteristics of streams and rivers, which has increased runoff from the watershed. Changing flow characteristics can result in the movement and transport of contaminants to downstream areas.

Progress Toward a Cleaner Minnesota River

Sediment and associated materials the Minnesota River carries have been implicated for having adverse effects on downstream receiving waters, including the Mississippi River and Lake Pepin. Lake Pepin is 59 river miles downstream of the Minnesota River (USACE 2022a) and is the largest lake on the Mississippi River (MnDNR 2022). Engstrom (2000) describes that since the 1830s when the area started becoming populated with nonindigenous settlers, the Minnesota River has contributed more than 70 percent of the sediments measured in Lake Pepin.

The Minnesota River attracted considerable attention in the late 1980s because of unhealthy fish populations, algal blooms, and sediment. In 1992, former Governor Arne Carlson announced an ambitious plan to clean up the Minnesota River, issuing a challenge to make it “swimmable and fishable” within 10 years. That challenge promoted many studies and efforts toward achieving the stated goal. Measurable progress has been made, but more work remains (MRBDC 2007; Steil 2002).

Ongoing efforts implemented at scales ranging from basin-wide to site-specific are leading to a cleaner Minnesota River. The implementation of best management practices, the Conservation Reserve Program, and the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program all have reduced the amount of sediment and nutrients reaching the river. Programs applied throughout the watershed and at focused locations have led to upgraded inputs from wastewater treatment systems, confined animal feeding operations, and other sources of materials that otherwise would have added to the pollutant load of the river. The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency summarizes much of the work that has been and continues to be done in the Lower Minnesota River (Minnesota Pollution Control Agency [MPCA] n.d.). While progress is being made toward a cleaner Minnesota River, the issues faced are complex and more needs to be done to successfully manage this important resource. To learn more about current work of the LMRWD, read about the planning effort to develop the Minnesota River Corridor Management Plan as well as daily operations for maintaining the nine-foot navigation channel.

Varied Uses Along the Minnesota River

Many lakes and wetlands are present along the floodplain of the Lower Minnesota River, and many are included within the Minnesota River Valley National Wildlife Refuge (MRVNWR). These lakes and wetlands provide important habitat for migratory waterfowl and other wildlife. The MRVNWR is complemented by Fort Snelling State Park, which includes most of the bottomlands along the last three to four miles above the confluence with the Mississippi River.

The Minnesota River was used mostly as a conduit for native populations until fur trading and other commercial operations increased its importance for transportation. The first steamboat to pass up the Minnesota River past Carver (Mile 36) was the Anthony Wayne, a Mississippi River boat, which came from St. Paul in 1850 (MRBDC n.d.). Steamboating on the Minnesota River was most active during the 10-year period from 1855 to 1865, with shipments occasionally extending upstream of Mankato (river mile 105). Much of the traffic was restricted to river stretches below Carver Rapids, which can form a barrier to riverboat passage when streamflow is too low. Maintaining the Minnesota River as navigable lingered for decades after the steamboat era, but the coming of railroads and their river-spanning bridges in the late 1860s ruined the idea.

During modern times, the 15 miles of the Minnesota River from Savage to the mouth are a multimillion-dollar transportation route as barges carrying grain, construction materials, and other products are pushed to and from ports in Savage, Minnesota. During the five years of 2008–2012, about half of the 10 million tons of material, worth more than 2 billion dollars, transported annually to and from ports along the Mississippi River in Minnesota were handled at the Savage, Minnesota, port along the Minnesota River (MnDOT 2014).

This transportation requires that the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) maintain a nine-foot navigation channel during nearly the entire open-water season (USACE 2022b). The USACE (2022b) states, “Channel maintenance is 100% federally funded except for short segments of the Mississippi River in Minneapolis and on the Minnesota River. Nonfederal sponsors are responsible for furnishing dredged material placement sites on those segments.” The LMRWD is responsible for disposing of this dredged material and must manage where to place it safely away from the river. It also creates a marketing opportunity for the large amounts of dredged sand and gravel.

The Minnesota River is also used for recreation with visitors hiking, paddling, and boating along portions of the waterway. To learn more about opportunities to get on the water or walk along the bluffs and view nature, visit our Recreation Page.